Are you or someone you love having thoughts of suicide? If at immediate risk, please call 911 or go to your nearest emergency department. Or you can get support from the Canada Suicide Prevention Service by phone, text or chat. Resources here.

On the day the world learned of Anthony Bourdain’s suicide death, journalist Andrew Solomon’s essay “Bourdain, Kate Spade, and the Preventable Tragedies of Suicide” was published in The New Yorker. Solomon, a professor of clinical psychology at Columbia University and repeat TED talk speaker on mental health, wrote about the pattern of highly accomplished people dying by suicide, and how it can both transfix and harm us.

That same week, the CDC reported that since 1999 U.S. suicide rates are up 30% and are now a leading cause of death. In Canada, the statistics have a similar direction. There is a narrowing in the ratio of male-to-female suicide rates, which reflects the accelerated increase in female suicide rates. In our military community, former Canadian soldiers are killing themselves at a significantly higher rate than that of the general population. In the weeks that followed the suicide deaths of Spade and Bourdain, a flurry of reports and opinions were broadcast, many promoting misleading conclusions and assumptions. I reached out to psychologists and psychiatrists at Medcan in search of clarity, hope and how to seek help.

“It assures the rest of us that a life of accolades is not all that it’s cracked up to be and that achieving more will not make us happier (…) Those of us who have clinical depression can feel the tug toward suicide amped up by this kind of news. The gap between public triumph and private despair is treacherous, with the outer shell obscuring the real person even to those with whom he or she had professed intimacy.”

Suicide is preventable. Help is available.

Suicide is far more complex than headlines make it out to be. Clinical research, however, is certain that mental health issues are a key component of factors contributing to suicide. “More than 90% of people who take their lives by suicide have an underlying psychiatric illness that is potentially treatable,” says Jodi Lofchy, MD, FRCPC, a psychiatrist at Medcan, the University Health Network, and an associate professor at the University of Toronto. “There are treatments available and life will look very different and well again. If you are suffering, reach out and get help. Concerned friends and family should also be aware of resources – from family doctors to emergency services – to connect their loved ones to.” With proactive medical screening, asking and monitoring through social relationships, suicidal feelings can be recognized, and addressed through the right medical channels.

Suicidal thoughts are a sign to seek help. Recognizing them is a sign of strength.

“People who have struggled with suicidal thoughts or have attempted suicide can, and do have fulfilling and active lives,” says Gina Di Giulio, LLM, PhD, Clinical Psychologist and Director of Psychology at Medcan. “Admitting how you are feeling to yourself, and then to others, is a sign of strength. Having the conversation with someone is not a sign of weakness; it takes incredible courage to open and admit to difficult feelings. Openness leads to accessing help that is available and can prevent suicide.”

With the right support, life will look very different, and well, again.

Suicide is often referred to as a permanent solution to a temporary problem. It is often considered when someone faces challenges or obstacles that have no sense of resolution at the time. Depression, relationship problems, addiction, financial difficulties – these are usually time limited or can be solved, says Dr. Di Giulio who works with clients using a problem-solving, structured therapeutic approach aimed at solving or ameliorating problems that clients often believe to be insurmountable. Finding and holding to hope is key. The number one predictor of suicide is a sense that of hopelessness; that things won’t get better. “Social isolation or seeing yourself as a burden to others can be a risk factor,” says Ricardo Flamenbaum, Ph.D., C. Psych., also a psychologist at Medcan. “Conversely, research shows that a sense of connectedness and belonging is an important protective factor.” Dr. Flamenbaum’s dissertation focused on identifying psychological predictors of suicide, and he has published research in the areas of perfectionism and chronic pain as well.

High performance is not a protective factor to suicide. Reaching out for help is.

Even the highest performing people are at risk to suicide. Michael Phelps, the most decorated Olympian of all time, has shared his battle with depression and suicidal thoughts. He has said how grateful he was that he didn’t take his own life. “Having a perceived sense of purpose is very important. However, it is also possible to be depressed or suicidal even if one has a purpose, so it is not deterministic in that way,” says Dr. Flamenbaum. “One of the challenges with depression is that it involves a distorted view of oneself, the world, the future. So even if one has very meaningful activities and relationships in one’s life, depression may cause the individual to fail to appreciate or recognize them.” Having a purpose, determining your why, having strong social connections – these are all important for performance and for imbuing meaning into your life. But they aren’t always enough of a protective factor against suicidal tendencies. Opening up and seeking support are.

Depression and suicidal thoughts can affect anyone

There are populations that are more at risk than others: having a history of suicidal thoughts or attempts, or clinical anxiety or depression can place someone into a higher risk category. Among vulnerable individuals, even just reading about suicide deaths can further increase risk. There are other factors contributing to one’s susceptibility to suicide: sleep and technology are just two to consider. Sleep deprivation has a devastating effect on mental health; 40% of adult Canadians suffer from sleep disorders. While habitual technology habits can create incredibly alienating cultures; isolation being another significant suicide risk.

Suicide is a public health issue. Clinicians, employers must be proactive.

In 2014, I wrote about the need to break down barriers to teen mental healthcare for Canadian teenagers for a cover story in Hospital News. The lessons then shared by the pioneering psychiatric teams at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre are the same as those shared by trailblazers in the U.S. today. “We need to beef up our mental-health system: we are not training enough clinicians, not getting enough clinics built across the country,” says Victor Schwartz, the chief medical officer of the jed Foundation, a suicide-prevention group, in Solomon’s article. “Many clinicians are untrained in suicide prevention. We need preventive public-health initiatives on managing depression and anxiety in the pre-crisis stage. Every school should have an approach—but so should every employer and every small town.”

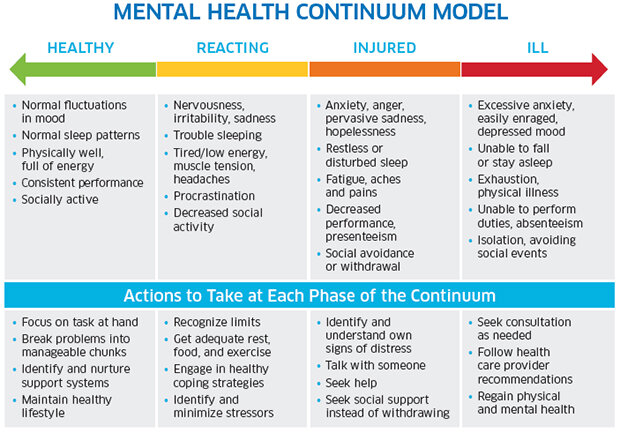

Figure 1: Mental Health Continuum c/o the Mental Health Commission of Canada.

Mental Health First Aid, understanding the Mental Health Continuum

Companies and schools are increasingly taking on the responsibility of looking out for their peers and colleagues through national organizational health programs like Mental Health First Aid, and others conducted by the Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety. The Mental Health Commission of Canada developed a mental health continuum model (figure 1) that illustrates the non-binary spectrum of symptoms people may exhibit, and the recommended actions to take at different stages.

Canadian Armed Forces (CAR) focuses on resilience

One of the ways the CAR is addressing the incidence of depression and suicide among its ranks is by designing training programs that focus on resilience. The CAR defines resilience as “the capacity of a soldier to recover quickly, resist, and possibly even thrive in the face of direct/indirect traumatic events and adverse situations in garrison, training and operational environments”. The Road to Mental Readiness (R2MR) mental health training recently launched an accompanying app that can be used for goal-setting, self-talk, mental rehearsal, tactical breathing, attention control and working memory, and allows users to build personalized scripts and scenarios to achieve personal objectives.

Understand the warning signs and how to reach help

As the stigma of mental health and suicidal thoughts fades, more people are talking about signs, symptoms and reaching out for help. May that discussion continue to shatter the misleading myth that if you ask people about suicidal feelings, it causes them to become suicidal. When really, any query from a place of concern can open an entirely new avenue to help, healing and, eventually, wellness.

Tania Haas also teaches post-traumatic growth meditation and movement to members of the military.

Are you in crisis?

Are you or someone you love having thoughts of suicide? If at immediate risk, please call 911 or go to your nearest emergency department. Or you can get support from the Canada Suicide Prevention Service by phone, text or chat:

Phone: toll free 1.833.456.4566 or the Gerstein Centre Crisis Line at 416.929.5200

Text: 45645

Chat: crisisservicescanada.ca

For residents of Quebec, call 1 866 APPELLE

Warning signs of suicide

Signs that might suggest someone is at risk of suicide include:

thinking or talking about suicide

having a plan for suicide

Other signs and behaviours that might suggest that someone is at risk of suicide include:

withdrawal from family, friends or activities

feeling like you have no purpose in life or reason for living

increasing substance use, like drugs, alcohol and inhalants

feeling trapped or that there’s no other way out of a situation

feeling hopeless about the future or feeling like life will never get better

talking about being a burden to someone or about being in unbearable pain

anxiety or significant mood changes, such as anger, sadness or helplessness

What to do if someone you know exhibits warning signs of suicide

Do not leave the person alone

Remove any firearms, alcohol, drugs or sharp objects that could be used in a suicide attempt

Canada Suicide Prevention Service by phone, text or chat (see above)

Take the person to an emergency room or seek help from a medical or mental health professional

Other resources

The Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention offers resources on suicide for survivors, those thinking about suicide, those who have been affected by someone who has attempted or died by suicide, and anyone who wants to help someone who has been affected in any way: https://suicideprevention.ca/

The Canadian Mental Health Commission offers tools, readings, information and contacts specifically linked to both suicide prevention and surviving a suicideand surviving a suicide loss

Distress and Crisis Centres can offer 24/7 support to those who are feeling suicidal. For a list of centres across Canada see https://suicideprevention.ca/need-help/

Listen to interview and/or read the book: Myths about Suicide by Thomas Joiner (2011)